Why Can’t Our Kids Write?

The Silent Crisis in Education No One Wants to Talk About

This article originally appeared in Minding the Campus in March 2024.

We need to talk about student writing.

For the past decade or so, I have worked with students to help them prepare essays for applications to America’s top colleges and universities. Many of my students have historically matriculated to Ivy League and other top-tier universities, and every year, we continue to send a handful of Invictus Prep students to America’s most coveted colleges. Yet, over the past several years, I have noticed an alarming trend amongst my seventeen-year-olds: no one knows how to write anymore.

Don’t get me wrong. There are always exceptions. Every year, several students will shine as the rest prove to be average. That is expected among any sample size of students—a normal distribution of IQ or however you would like to measure intelligence. But what is alarming is not that we are not producing twenty-first century Shakespeares en masse—for that is never the case in any society. What is alarming is that what constitutes “average” writing quality is starkly declining.

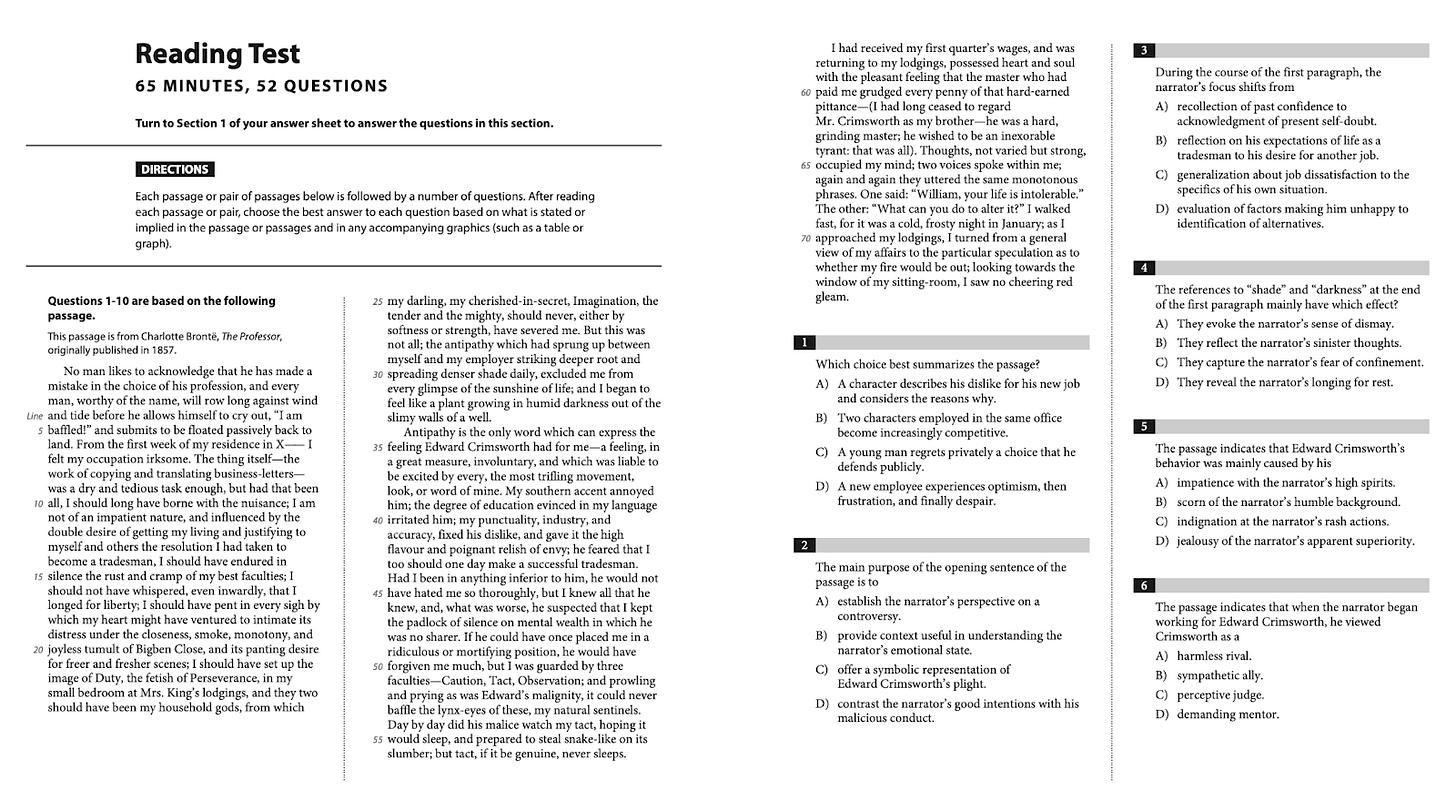

Years ago, many of my students could walk into an SAT testing center and produce a hand-written two-page essay in less than an hour. This sort of skill was not the exception but the norm. Indeed, back when I applied to college in 2015, the SAT required an essay portion that proved to colleges that you were at least capable of stringing basic thoughts together. Not anymore. In 2021, in the wake of the pandemic, the College Board dropped the essay from the SAT before overhauling the exam entirely in 2024. The new version of the SAT is a chilling reminder of the continual erosion of Gen Z’s reading and writing skills. Compare a “literature” reading task from the previous 2016 SAT with the new 2024 digital version:

In the 2016 SAT, students are asked to read and digest a longer chunk of text—often from great literary works—and answer questions that require them to deeply comprehend the subject in question. The new 2024 SAT, however, catering to the abysmal Gen Z attention span, asks students to sit with less than a paragraph of text, shows them exactly where to find the answer to the question, and then prompts them to move on without giving each passage a second thought. And while literature still occasionally appears on the new digital test—though not as consistently as on the previous exam—test takers are primarily fed easier passages from our contemporary world, removing the necessity for students to learn how to understand older literature.

I have written extensively about the importance of reading great literature to become a great writer. Most of my students, of course, are not training to create the next Great American Novel. Most of my students will continue on to secure professions in tech, medicine, law, or business. But every one of these students will benefit from good communication skills—and every one of these students is currently being failed by an education system that deemphasizes reading and writing. The difficulty of the math questions on the SAT, after all, has stayed consistent across tests.

Why, then, dumb down the reading section? The answer, of course, reflects the priorities of our society: College readiness no longer entails the ability to think critically or to write well.

The problem of student writing quality extends, of course, beyond the sorts of questions that appear on the SAT. AI tools have virtually eliminated the necessity for students to learn anything about grammar, sentence structure, and the eloquent expression of ideas. Every single one of my students has Grammarly preloaded on their browsers, a tool that cleans up spelling and grammar from tasks as menial as writing emails to those as monumental as drafting the college essay. Students use ChatGPT to obtain summaries of longer texts for English classes and tools such as Studocu to generate AI notes on any topic imaginable. Years ago, I could ask a student to write a paragraph in front of me during a meeting, and within moments, we would have a group of sentences in front of us. Now, every student asks for time to “think about it for homework”—most likely because they do not want me to know they will not be the ones doing the thinking. As a result, many students will graduate high school without the slightest knowledge of how to write a sentence without AI tools. And these are not students who will go on to blue collar professions or who did not have access to educational resources—which is a separate problem of its own. The students in question here are students who have access to everything they need—students who come from affluent backgrounds and will graduate from four-year universities. These students have not been failed by a school system that cannot provide them with adequate resources due to a lack of funding. These students have been failed by a society that has simply devalued the importance of the written word.

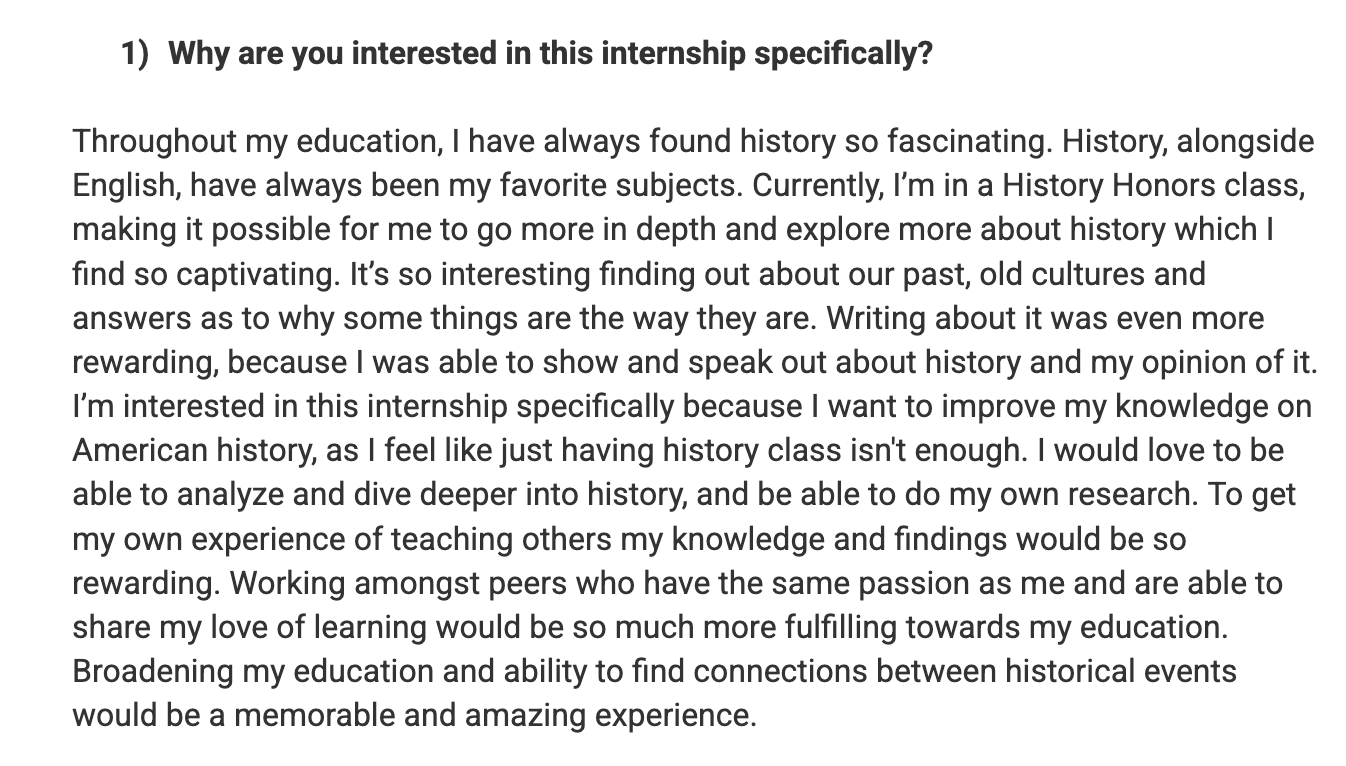

The result is that many of my students can no longer produce coherent writing. Take this example from a sixteen-year-old student applying to summer internship programs:

This writing sample is not from a student who plans to study STEM or learned English as a foreign language. As this student tells us, her favorite subjects are history and English. This student has gone through almost three years of high school and has developed a predilection for the humanities—but can barely write a coherent thought. And even putting abysmal sentence structure aside, we learn virtually nothing from this essay about who she is or why she is interested in the internship—most of her sentences contain nothing but meaningless fluff. But this is not her fault at all—it is the fault of a school system that no longer emphasizes strong critical thinking skills, for it is likely that no one has ever sat her down and taught her what a sentence is really meant to do—that is, communicate an insightful thought. Yet, without exposure to great sentences, how can we expect students to generate their own?

As my juniors scramble to prepare their essay materials for this coming college application cycle, I worry that few, if any, students will be able to produce writing worth reading. And as I attempt to stuff seventeen years’ worth of writing pedagogy into several meetings with the kids, I cannot help but wonder why we have decided that students no longer need to be able to write to succeed in this world. Good writing, after all, is the primary proxy for strong critical thinking skills—without it, we will have raised a generation that does not know how to think for themselves.

So let’s not ignore what our society has done to diminish the importance of good writing. Yes, the damage has been done, but the cause is not totally unsalvageable. Parents, read your kids a book. Force them to diagram a sentence. Do not claim that they can go into a STEM profession without knowing how to write. The more we show students how important it is to write well, the faster we can return to a world where a student can sit through an entire Charlotte Brontë novel and, yes, write an essay about it without the help of ChatGPT.

Enjoyed this post? You can Buy Me a Coffee so that I’ll be awake for the next one. If you are a starving artist, you can also just follow me on Instagram or “X.”

I have some first hand experience with abysmal writing and reading expectations in schools--I am a 5th grade teacher.

First, regarding reading. There is a major push in schools to focus on short, contemporary, and informational text. I was told by a Language Arts Specialist that I should never "waste time" with anything longer than 3 pages long. And let's be honest: modern short, informational writing demands so much less brain power than the greatest works of literature. I do my best to counter this nonsense in my own class (we read ten novels over the course of the year--we're just starting Treasure Island now), but there's sadly only so much a single teacher can do against this wave of stupidity.

Second, regarding writing. There's a huge push to get kids to write longer pieces as fast as possible. 1st graders are expected to write a paragraph. My 5th graders are expected to write a multi-paragraph essay.

You may wonder, "what's wrong with this?"

Well, the students can't write a coherent sentence yet. And so you get what you show in your example: lots of words that are empty, with very little substance or craft. My own fifth graders came to me unable to explain what makes a complete sentence. And yet, they've been writing full paragraphs for years.

In short, we are skipping the basics, the foundations. We ask they put up a large word count and don't bother to ask: does it mean anything? Are the thoughts organized? How do you move from one idea to the next, carefully leading the reader through an intelligent guided tour of your thoughts on the subject? Are the sentences themselves crafted with intelligence and care?

And now, with the advent of AI into the sphere, the problem will only get worse and worse.

Good writing is a product of frequent book reading. I don't think kids read much today other than abbreviated text messages.