Welcome back to the Pens and Poison The Waste Land analysis series! Today, we’ll be looking at Part 1 of this monumental 20th century poem about the futility of human intimacy. If you missed my intro to The Waste Land, you can read it here.

You can also watch my analysis of Part 1 of The Waste Land here.

In the intro and backdrop to The Waste Land, we learned about how the poem is a reinterpretation of the Fisher King myth. Today, we’ll discuss how this mythical figure plays into the first part of the poem and what this might tell us about desire in The Burial of the Dead.

Let’s start with the epigraph. A poem’s epigraph is typically a short quotation that provides a lead-in to a poem’s overall theme or message. Eliot chooses a rather abstruse epigraph for his poem—in keeping with the poem’s overall abstruse nature, of course—and gives us a quote partially in Latin and partially in Ancient Greek. It’s an excerpt from an early Latin satirical piece by Gaius Petronius called—quite aptly—The Satyricon.

‘Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Σίβυλλα τί θέλεις; respondebat illa: άποθανεîν θέλω.’

There are several different translations to the excerpt above, but here’s my own translation based on my limited working knowledge of Latin and Ancient Greek:

“For I saw the Cumean Sybil hanging in a jar with my own eyes, and the boys asked her, ‘Sybil, what do you want?’; she responded, ‘I want to die.’ ”

The myth of the Cumean Sybil follows the story of a woman who was granted a wish from the Greek god Apollo. Her wish is simple: to live for as many years as there were grains of sand on the beaches of the Earth. In making her wish, however, she forgets to ask Apollo for eternal youth and now must live out her immortal days rotting from old age, suspended in a jar to survive. In a somewhat morbid turn of events, Sybil can only then think of death.

Eliot could not have chosen a more suitable: at once, he presents us with the poem’s main themes: death, futility, desire.

From there, we have a dedication to Eliot’s friend and fellow poet Ezra Pound, who helped edit to the poem down to the form we know it in today:

For Ezra Pound

il miglior fabbro.

We’re already reading in four languages before the poem even begins. Talk about modernist pretensions! In his dedication, Eliot communicates his gratitude to Pound, whom he calls “the better craftsman.” The Italian in the dedication might at once be an homage to Eliot’s favorite poet Dante Alighieri and an allusion to Pound’s admiration for the Italian language and culture, which famously and somewhat unfortunately culminated in Pound’s support for the Italian fascist party under Mussolini.

Yet despite Pound’s less-than-perfect politics, his skills as an editor are unparalleled. Pound was responsible, for instance, for the poem’s current title, The Waste Land, which, at his instigation, Eliot changed from his original title He Do the Police in Different Voices, a reference to Charles Dickens’ Victorian novel Our Mutual Friend. Eliot’s original title was meant to capture the many overlapping voices we see throughout the poem, but the title The Waste Land more succinctly represents the poem’s essence.

The Waste Land famously opens with an allusion to Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, a medieval collection of stories that center around a pilgrimage to Canterbury. Chaucer’s work opens with a plea to springtime—“Whan that April with his showres soote”—and through its opening lines sets up the theme of hope through the rebirth of life in spring. The Waste Land’s opening line—“April is the cruellest month”—takes Chaucer’s idea of spring as rebirth and turns it on its head—spring is no longer about hope; in Eliot, rather, spring becomes the emblem of futility and cruelty. The season no longer embodies the blanket of safety that it does in Chaucer—in Eliot, in fact, it is now “winter that kept us warm.” The narrator of the opening stanza of The Waste Land—perhaps the figure Marie—experiences a fear that can only be released by the act of sledding downward. When Marie feels frightened, her cousin negates her fear and isolation by taking her sledding in the mountains, replacing her fear with a sense of freedom. In one respect, Eliot seems to be saying, freedom assuages fear. Yet freedom from what? Desire, perhaps? That certainly seems to be the landscape that Eliot presents us with at the outset of the poem.

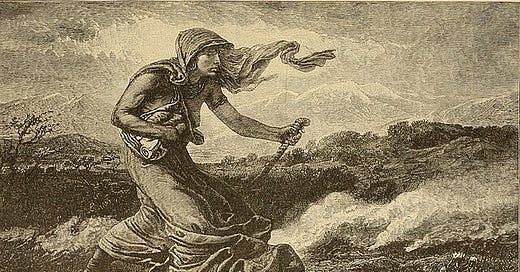

The second stanza of the poem—widely known as “The Sermon Stanza”—presents an alternate take on fear through allusions to the Book of Ezekiel and Ecclesiastes. At this stage in the narrative, Ezekiel establishes a prophetic authority within the poem that grants both the prophet and the reader the feelings that were earlier denied them in the Marie episode. While Marie sleds downwards and releases fear, the prophetic stanza explores the act of rising—almost a direct juxtaposition to Marie’s release of anxiety whilst sledding. Here, fear culminates in “a handful of dust,” a reference to the famous “all is vanity” from Ecclesiastes, which highlights the futility of old age and argues that all human experience must end in the same way.

Intimacy in The Waste Land therefore becomes intrinsically bound up with the human experience of fear. If you recall our earlier analysis of the Fisher King, you’ll remember that one of the most famous representations of the Fisher King lies in Wagner’s opera Parsifal. It is no accident, then, that the end of the sermon stanza Eliot quotes directly from Wagner:

Frisch weht der Wind

Der Heimat zu

Mein Irisch Kind,

Wo weilest du?

My translation of these lines runs thus:

Fresh blows the wind

To the homeland

My Irish child,

Why are you weeping?

These lines appear twice in the opera, and with the exception of four preceding lines that establish the nautical setting of the first act, these words open the initial act of Tristan und Isolde and introduce a new motif within the opera that we do not find in the prelude; later on, sung by the same young seaman, they also open the second scene of the opera.

Tristan und Isolde? But isn’t The Waste Land based on Parsifal?

My theory is that Eliot quotes from Tristan rather than Parsifal because the former opera more accurately captures the theme of the futility of desire and the unnaturalness of intimacy—the main ideas of The Waste Land.

The sailor’s song in Tristan establishes a powerful sense of erotic longing for an unattainable beloved;

taken by itself, the sailor’s song has no obvious mal-intent: the seaman sings “of his separation from his own Irish sweetheart,” a lover we never see onstage and who is removed from the storyline entirely; the moody Isolde, however, overhears the sailor’s song and immediately takes his lament as an invitation to rage against Tristan in the memory of her own betrothed, the Irish knight Morold, whom Tristan has slain. As she overhears the sailor’s song, Isolde, starts up auffahrend, the German irritable. Her next reaction—sie blickt verstört um sich (she looks around in bewilderment)—suggests a sense of confusion and mental distress that anticipates the ignorance of Eliot’s Hyacinth Girl (whom we will meet in just a moment).

When we hear the text of the sailor’s song for a second time in the following scene, we find that Isolde has undergone a change of heart: the description that Wagner gives of Isolde runs thus: deren Blick sogleich Tristan fand und starr auf ihn geheftet blieb, dumpf für sich. Her gaze lands immediately on Tristan and remains fixed; she sings hollowly to herself. The sailor’s song thus represents both “bereavement” and “passion” for Isolde, and her initial two lines in response to seeing Tristan—“Mir erkoren/Mir verloren” (both lost to me and destined for me)—reemphasize this dualistic dimension of love and suffering. Wagner borrows the thematic material of Mir erkoren/Mir verloren from his prelude and then reuses the same bars in the famous Liebestod in the final act of his opera. Wagner’s powerful leitmotif of desire and longing thus associates itself with the innocent sailor’s song and consequently begins to muddle innocence with sexual experience.

Which brings us swimmingly to Eliot’s Hyacinth Garden.

Eliot is quite famous for his use of flowers and gardens as metaphors—you see his “rose garden” later in The Four Quartets’ opening poem, “Burnt Norton.” Gardens in literature have long been symbols for paradise, innocence and beauty, and they are often used metaphorically to represent societal decay—think of John Milton’s epic Paradise Lost, which Eliot was almost certainly intimately familiar with. In Eliot’s Hyacinth Garden, the love between the Hyacinth Girl and her lover possesses a sort of artificiality—one that is closely reminiscent of the love that develops between Tristan and Isolde, who only fall in love after they both drink a love potion.

At the tail end of the “Hyacinth Girl" episode comes another quotation from Tristan und Isolde, this one taken from the opera’s third and final act: Oed’ und leer das Meer (Desolate and empty is the sea). The “Hyacinth Garden” passage is thus framed by these two passages taken from Tristan und Isolde, highlighting the opera's importance to the work—or, at least, to these few stanzas. Curiously enough, this line is sung by a tenor in the role of a shepherd who usually doubles in the opera as the young sailor; in performance, therefore, the roles become reminiscent of one another.

At this point in the opera, Kurwenal, Tristan’s companion and vassal, and the shepherd are in the castle garden (there’s our garden again), looking out at sea to anticipate the coming of the ship that is to carry Isolde, the only Ärztin, or nurse, who will be able to heal the wounded Tristan—again, we revisit the theme of decay and healing and are reminded of the Fisher King. Kurwenal asks the shepherd to “pipe his merriest tune” should he apprehend the coming of Isolde’s ship, but the shepherd instead replies, after an extended pause that lasts five bars, that the sea is desolate and empty—our quote in the poem.

The crucial thing to note here is that Isolde is not only separated from Tristan as a lover from a lover but also as a nurse from a patient; Tristan’s wound thus becomes associated with sexual guilt—for he has been wounded by the sword of Melot, a knight who serves King Marke, the man Isolde was supposed to marry upon the ship’s arrival to Cornwall. When Tristan and Isolde are discovered making love in the garden in the previous act, Tristan succumbs to Melot’s sword because of the guilt he feels at having been with Isolde. What is even most significant for our purposes is the explicit link that Tristan’s wound creates between himself and Parsifal’s Amfortas—Eliot’s Fisher King.

In both cases, the wound is one of “sexual guilt” and thus sets up the motifs we find in the Hyacinth Garden episode and elsewhere in the poem. The difference, however, between Eliot’s barren world and that of Tristan und Isolde is that in the latter, hope arrives in the form of Isolde the healer and temptress, albeit too late, and leads to a more optimistic “transfiguration” through the singing of her Liebestod, Isolde’s eventual love-death. In Tristan, death is the necessary prerequisite to the fulfillment of an otherwise unattainable desire, the bypath to change and transfiguration and, ultimately, a better future.

Death allows Tristan and Isolde to reveal their true feelings for one another and escape the artificial and substitutive world which they have been previously subjected to. With the resolution of the opera’s opening Tristan chord in the Liebestod, Isolde’s emotions, stifled unnaturally for over three hours by Wagner’s initial rejection of the standard dictates of harmonic chord progression, become not only possible but also genuine. She experiences an intense emotional episode and comes to terms with the reality of her love for Tristan: she can love him only in the wake of her own death.

In Eliot, the Hyacinth Girl’s failure with lover mirrors Tristan and Isolde’s own failed relationship in terms of a common sense of unfulfilled longing: the moment that the Hyacinth Girl apprehends the abortive nature of her relationship with her unspecified lover, “she cannot speak” and virtually loses all conscience of her surroundings. She exists in a paralyzed limbo much like Isolde, yet unlike Isolde, there is no hope for her of transformation or redemption, for we leave her in the wake of silence, desolation, emptiness. Unlike Tristan and Isolde, therefore, who attain meaning in their lives through their mutual destruction, Eliot’s lovers cannot consummate their love through any sort of transformation and thus find themselves facing an utter loss of meaning in their relationship—“I knew nothing.” Yet after a continued strain of bleakness in tone and imagery, the male figure in the garden looks into the “heart of light.” Perhaps a shred of hope? Yet as if oblivious to the failure of his sexual relationship, his hope is fleeting: he blindly convinces himself that there is hope for himself and the Hyacinth Girl, resurrecting their love in a most unnatural fashion. The phrase itself—“the heart of light”—recalls Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, from which Eliot notably intended to extract the phrase “Mistah Kurtz—he dead” for The Waste Land’s epigraph before it became the epigraph for The Hollow Men instead.

The alteration of the phrase—from heart of darkness to heart of light—suggests a false hope for a better future and an artificial method through which this hope can be attained. The tragedy of the world of the Hyacinth Girl is thus that these lovers, and, indeed, lovers in general, can no longer recognize the beauty of genuine human connection and opt instead to content themselves with an empty erotic experience that culminates in silence.

Later in the poem, there will be hope for redemption—through the themes of drowning and water that we are introduced to at this stage of the poem.

Here we come to Madame Sosostris, the famous clairvoyante with a bad cold, who, through her Tarot cards, brings us the idea of drowning as a symbolic transformation. During a Tarot reading, she draws the card of the Phoneician Sailor, exclaiming “fear death by water.”

Eliot likes sailors.

At this stage, in fact, we have even more of them. Eliot invites us to recall Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest—a play about drowning and shipwreck—through the lines “Those are pearls that were his eyes,” an allusion to the drowning of Ferdinand’s father. Yet as many things in The Waste Land, the motif of drowning will soon become inverted and perhaps become a positive. Don’t forget to pay attention to the nautical imagery throughout—it will come back in later sections of the poem.

Finally, we come to the famous closing stanza of “The Burial of the Dead”: Eliot’s famous “Unreal City,” which he himself claimed was a reinterpretation of Baudelaire's Fourmillante Cité—“swarming city.” We have yet another reference (Eliot likes those) to Dante’s Inferno in the line “I had not thought that death had undone so many,” wherein Dante visits Hell and witnesses many dying souls as he progresses through each of the nine circles of Hell. The narrator of Eliot’s poem roams through a similar Hell—yet here, Hell is conceptualized in the form of the London city streets. We revisit the theme of death and old age in conjunction with the garden:

‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

‘Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

‘Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

Does Eliot thus suggest that we can attain growth from death—rebirth from death? Morbid, yet very much in keeping with the parallel to Tristan und Isolde.

Finally, the closing line to The Burial of the Death (in yet another language):

‘You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!”

One more Baudelaire reference, this one bringing us back to the poem’s opening line through the idea of repetition and the digging up of memories. Talk about rebirth.

So is this a poem about death and the futility of desire? Absolutely. Through the poem’s many allusions, Eliot takes us through the decay of human relationships and the human experience. At this stage in the poem, there is no hope for redemption, yet as we'll see later, Eliot will invite us to consider what we must do to resurrect human relationships and find meaning in decay.

Stay tuned for my next installment of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land analysis, where we’ll dive further into The Waste Land’s exploration of decay in the second half of the poem—“The Game of Chess.”