The Strange Death of Literary Men

Men have abandoned reading. The publishing industry has abandoned them.

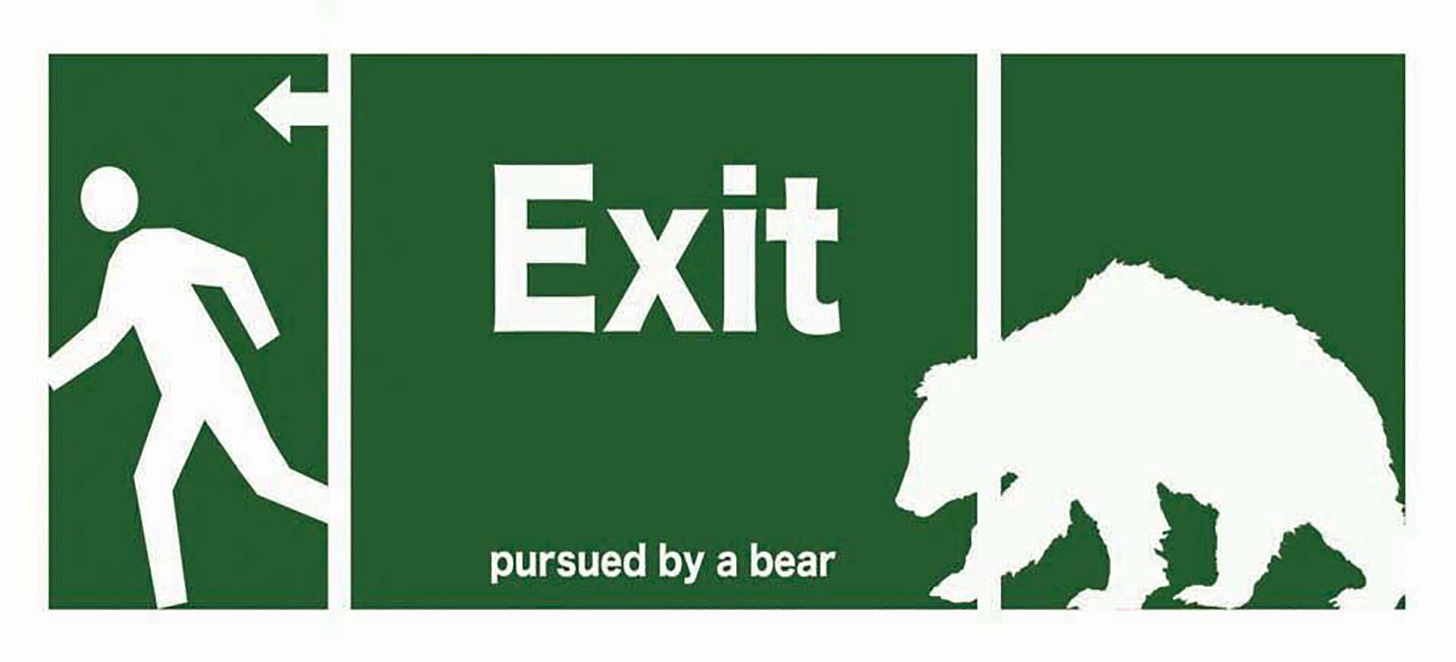

In my senior year of high school, I took a trip out to Stratford-Upon-Avon, the birthplace of English literature’s favorite Bard William Shakespeare. After fraternizing with a group of middle-aged volunteers in Elizabethan-style dresses, I headed to the gift shop and purchased the following plaque:

My mother, who has only read Shakespeare’s most popular plays in Russian translation, was stumped. When I proceeded to explain to her that the sign was a riff on Shakespeare’s most infamous stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear” from A Winter’s Tale, she laughed. Walking back out into the open past the town’s characteristic hut-like houses, I announced that I would hang the plaque above my dorm room as a test for any man who wanted to date me: if he did not properly identify the reference, he had no business encroaching on my life.

I went to a predominantly STEM K-12 school and had only ever been exposed to men in STEM for the majority of my early life. Unlike many of the other girls in my class, who had entered their first relationships by age seventeen, I had no romantic interests at school because I could not comprehend dating someone who had zero understanding of the most important facet of my existence: literature. Instead, I daydreamed of a world where intellectuals stayed up until the early hours of the morning discussing Dickens and Dostoyevsky. This was the world I was promised when I hopped on a plane to New York City and arrived at Columbia University. This was the world in which I hoped to identify a future life partner with whom I could share a vast library and chat about Hemingway over dinner.

I still laugh at seventeen-year-old Liza, but at least she had some lofty goals.

I won’t get too far into my personal life here, but what happened next upended my entire worldview. For the first seventeen years of my life, I believed that the reason I had never met a man who appreciated literature was because I spent my days in a sequestered, STEM-focused environment. While that certainly didn't help, what I failed to realize was that this was not a Liza’s-high-school-exclusive problem. Instead, as I navigated Columbia, I was shocked to learn that the vast majority of young men I encountered—men who must have done something right intellectually to have earned their ticket to Columbia—had never picked up a book of fiction in their lives outside of class assignments.

Somewhat horrified and still myopic early on about my dating choices, I proceeded to date a series of effeminate men—the only ones I could find who cared an iota about literature. These men came, as one might expect, with their host of mental health problems and, to the chagrin of my conservative parents, severe commitment issues. By the time I hit my senior year of college, drained from recovering from serial, short-lived relationships with so-called “literary men,” I met an engineer at a Russian-Jewish event whose first announcement to me was that he could not stand Dostoyevsky and preferred the film version of Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog to the book.

Initially repulsed by his disdain of literature, I quickly warmed to him and found something else in him alluring. There were other problems, of course (as you might expect with any college relationship), but for the first time in my life, I experienced what it was like to go on a date with a more masculine man.

Then I knew that it was not necessary for a man to be a “man of letters” in order to be a good life partner.

These days, I live with the love of my life—a man who has read maybe half of a Shakespeare play in the SparkNotes “translation” and told me on our first date that he is “too ADHD for reading.” I’m working on his literary edification every day, and I would not trade him for anyone in the world, but reflecting on my own experiences in the dating world, I’m still puzzled by the seemingly-impossible quest of finding a stable, family-oriented man who is interested in literature. If I had to guess, I’d say I’m the only woman who has been affected by this peculiar cultural phenomenon. Men in our society are no longer interested in literature.

In The New York Times last week, David J. Morris observes the alarming decline of literary men in our culture. Morris, somewhat erroneously, attributes the decline of male interest in literature to the emergence of the “manosphere,” a conglomerate of online “masculinity” communities run by poor role models such as Andrew Tate and Joe Rogan. While I do not disagree that Tate and Rogan are not quite paragons of virtue, I see this sudden interest in these communities not as the cause of the declining interest in literature among men but as the result: if men do not have good books to read, they will, instead, turn to online subcultures that only reinforce what Morris might call their “toxic masculinity” (though I disagree wholeheartedly with this terminology—these days, men need to be more masculine, if anything).

While Morris correctly identifies a severe problem in men’s lack of engagement with literature, he completely misattributes the cause of the problem and demonstrates his fundamental lack of understanding of any potential solution by claiming that “young men should be reading Sally Rooney and Elena Ferrante” and that he “welcome[s] the end of male dominance in literature.” Taken as a whole, his argument runs thus: we have successfully ended male domination in literature, we have amazing books written by women, yet men are missing out on these books because they’re too busy playing video games or watching porn.

The moment I read the line about Rooney and Ferrante, I knew the entire argument was flawed. (You also know he’s wrong because he comes from the willfully-ignorant strain of leftists who are genuinely puzzled by the Black and Hispanic male vote for Trump.) I am a woman. I would rather jump off a cliff than entertain a single word of the Jew-hating, intersectional feminist Sally Rooney. I have not read Ferrante, but from what I know of her, she writes stories about marriage and childbirth—stories that women care about. I grew up with a voracious reader of a brother, whose favorite novel is Crime and Punishment—a book that deals predominantly with male psychology—and who routinely reads high fantasy and sci-fi novels such as Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings or Frank Herbert’s Dune. I live with a man who is far more likely to enjoy Notes from the Underground than The Bell Jar. The solution to the cultural problem of male fiction illiteracy is not to shove female-centric novels down the throats of men—though, of course, there is value in these books for everyone. It is to create books that men would read.

Unfortunately, with Rooney’s intersectional feminist coalition dominating the publishing space, men are no longer writing books for men—or for anyone else, for that matter. A survey conducted by Lee & Low Books found that close to 80% of publishing professionals are white women. Because this demographic dominates the publishing space, it is no accident that books by and for men are no longer being published. Even Morris acknowledges that men are being pushed out of literary spaces, citing novelist Joyce Carol Oates’ observation that “a friend who is a literary agent told me that he cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good.” Over on my Instagram page, where I post videos about literature, a fan wrote to me expressing his discontent after citing several of the above statistics at a writing conference and being dismissed by the panel of agents, who claimed that it was not a problem that men were no longer being published: the pendulum, according to one agent from Curtis Brown, the literary agency that once represented the novels of Ayn Rand, had simply swung the other direction and was correcting for previous injustices against women. Despite this pitiful attempt to justify the actions of publishing professionals, the fact is clear: the publishing industry actively discriminates against men.

While men might be inherently more drawn to non-fiction or, as Morris suggests, video games and pornography, I don’t believe it’s fair to completely dismiss the value of reading fiction in men, nor is it correct to say that only the sort of effeminate men I encountered at Columbia can connect with literary fiction. Many of my literary idols—T.S. Eliot and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, for one—were men who held staunch traditional values and were inspired by centuries of literary tradition before them. Men have always written literary stories about wars and conquests, technology and science, travel and adventure. But what stands out about these stories is not that they concern male-centric topics or that they were written solely for men. Many of my favorite authors are men, and their stories are special not because of a military backdrop or an exploration of masculinity but because they hold something for everyone and speak to universal truths of the human condition—truths that transcend gender boundaries.

Great literature should ideally have something for everyone. I do not disagree, therefore, that men should be giving books written by women a chance, but those books are not Sally Rooney’s Normal People or Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist—they are George Eliot’s Middlemarch or Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, books that speak to universal truths regardless of gender. By policing who and what gets published, the hegemons of the publishing industry encourage one-sided stories that focus on the female experience and do not have much to bring to a male readership. It is no accident, then, that men have been pushed out of the literary world almost entirely and no longer read fiction. It is no accident that among a group of students who are supposedly America’s brightest and best future thinkers, I met few men with a genuine interest in literature. It is no accident that men don’t read, and unless we begin to regard literature not through the lens of gender parity but through the lens of merit, we will have lost multiple generations of thoughtful, introspective men.

I routinely carp about publishing’s DEI problem, but I am, somewhat sadly, lucky enough not to have been born a man—for that would mean to sacrifice my dream of becoming a published author entirely. That is not fair in the least to my fellow male authors, who, if let into the publishing world, might have a genuine shot at restoring male readership and balancing the equation. The same women who complain that women were historically shut out of publishing are now doing the same to their male counterparts, and until we let men back in, we will, in fact, face a prolonged dearth of literary men.

Men—don’t abandon fiction. The fictional world needs you now more than ever, and the more men we have reading and writing, the more we can convince publishing companies to abandon their ways and give a voice to everyone.

I met a literary agent at a friend’s birthday party a few years ago and asked her if down the line I could ring her when I finish my book. She said yes, then told me “we’ll have to check your twitter and social to make sure you aren’t racist or anything first.” I laughed and said “yes of course.” She then added “you are a white guy after all,” and took a sip of her white claw.

This is my only interaction with anyone in fiction publishing. At first I thought it was just a joke. But now I’m not so sure!

Thank you for this piece - it echoes a lot of things I think about every day.

For myself, a lifelong avid reader, it’s getting harder and harder to find books to be excited about. My beloved Science Fiction genre has been utterly ideologically hijacked. Only Baen (for the most part) still publishes “classic” style SF, and they can’t publish everyone. I find myself reading a lot more nonfiction than I used to because much of what is published in fiction just doesn’t interest me. But for the younger generations of boys and men?

When I was starting out as a YA librarian 24 years ago, one of the great concerns in the profession at the time was the decline in reading among boys and what we could do about it. We talked about the male brain, “rules and tools”, why boys & men often prefer nonfiction (and why that’s OK), how we needed to hook them early with action, war, sports, cars, comics - whatever was needed to make reading a part of their lives. I routinely kept everyone from Jack London to Robert E Howard to Alexandre Dumas to Ernest Hemingway in my YA collection knowing that if I could fishhook them with Percy Jackson or Mike Lupica, I could maybe lead them down those roads eventually.

But of course, we (as a profession) did…nothing in the end. By 2012 or so “girl power” was the only thing that mattered and social justice ideology had begun its blitzkrieg-like takeover of YA publishing (and publishing in general, as you so aptly point out in your piece). Providing video game tournaments became more important than reader’s advisory and, well...those boys are now the men you speak of. They’ve been told that “Twitter is reading!” and quite possibly have never even had to read a book for school. Little wonder that they substitute online garbage for edification. We kind of told them to, in so many words and actions. And now we have a lot of disaffected young men who won’t read, and from what I see in the library every day, the future in this case isn’t too bright. We hear so much shouting about how “children need to see themselves REPRESENTED in the books they read!!!!!!” Unless they’re little boys, or teenage boys, or young men.

I have a fair bit of guilt about my 18 years as a YA librarian. We let a lot of things go down the wrong roads, and there were a lot of places I should’ve spoken up louder. But the fact that creating confident, strong adult readers has devolved so badly is the worst part of it.