In 2019, a banana duct-taped to a wall sold for $120,000. This singular moment in our culture—the exhibition of Maurizio Cattelan’s “Comedian” at Miami’s Art Basel—captured global attention and quickly sparked a debate about the nature of art in the 21st century: in a world of gross commodification and infinite possibilities, can anything be art?

Theodor Adorno, the Frankfurt School philosopher who decried the rise of the “culture industry” and warned us of this very decline in artistic merit nearly a century ago, might have the answer (spoiler—it’s a “no”). While Adorno was more a philosopher than an artist, his interdisciplinary cultural critiques have made him a household name in many artistic circles, and if you’ve ever studied the great thinkers of the 20th century, chances are you’ve heard the name of this idiosyncratic German scholar. Born in 1903, Adorno was a Neo-Marxist theorist who coined the term “the culture industry” to describe the commodification of art in the second half of the 20th century. While I am usually quite skeptical of anyone who proclaims themselves to be a Marxist (the ideology has led to countless failed societal experiments and, in the modern world, is more a stand-in for intellectual carelessness than a rigorously-tested philosophy), Adorno raises some legitimate concerns about the commodification of arts and culture and argues that the capitalist machine has turned art into a factory-produced commodity that has lost all vestiges of uniqueness. Today, we remember Adorno as something of an elitist—certainly, his insistence that the films of the 1960s were unabashedly derivative and that jazz music lacks originality as a genre does not exactly help his case1—yet in identifying an originality-based standard for a given work of art, Adorno makes an important claim that holds universal relevance: not all art is “good art.”

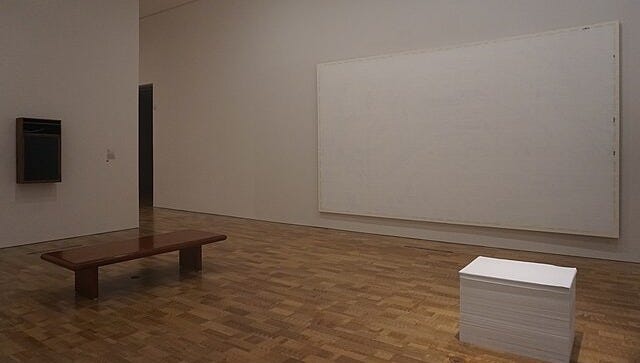

Indeed, in our postmodern universe, we are taught the bizarre maxim that anything can be art. Pioneered in the 20th century by Arthur Danto and Marcel Duchamp, this unsettling notion became mainstream as early as the 1920s with the emergence of quasi-nonsensical texts such as James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and oddly-silent chamber music pieces such as John Cage’s 4’33”. Danto, an art critic and professor of art history at Columbia University, believed in an “anything goes” approach to art that was dictated primarily by the whims of art students and museum curators. While this notion might have seemed amusing or even revolutionary in the early 20th century to someone like Duchamp, who famously submitted a signed urinal for the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, by the turn of the 21st century, artists had fully internalized this subjective approach to their craft and created a world where the notion of “good art” might well be obsolete. Walk into an art museum today, for instance, and you’ll probably be accosted with something like this:

Is it art? Is it a joke? No one knows, of course. The bench is likely part of the exhibit, too, as is that white block that looks oddly like a stack of paper towels in a public bathroom. Perhaps, as the French postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard might suggest, the very point is to reflect the absurdity of modern life, but Duchamp made that same point over 100 years ago with his infamous urinal, and, for God’s sake, a good work of art might do the same!

So while I don’t agree with Adorno’s cryptic disdain of jazz (I’m listening to Duke Ellington as I write this piece, in fact, and am convinced that Adorno simply didn’t care to understand the genre), Adorno might have a point about art: much of modern art is unoriginal and derivative. And whether you believe capitalism is to blame, the commodification of art has undoubtedly placed a damper on creativity. Marvel produces the same superhero movie every year, and Taylor Swift writes the same song 20 times over. High school English teachers are replacing novels with Kendrick Lamar songs, and artists with real technical skill pale in the face of their kindergarten-channelling counterparts. Now, more than ever, as we face a crisis of the arts, the question becomes whether we can salvage artistic freedom and genuine creativity.

Perhaps we can look to Adorno for an answer.

In the Dialectic of Enlightenment, a work co-authored with fellow Frankfurt School intellectual Max Horkheimer, Adorno argues that art has become standardized to the point where it appeals to all types of consumers rather than catering to a niche audience. In other words, mass media—a term that Adorno uses virtually interchangeably with his concept of “the culture industry”—has become mechanical. Adorno’s most famous (and most controversial) example is jazz, a relatively simple genre of music that, according to him, does not challenge existing social standards and only repeats a standard set of motifs and formulas. Jazz music, in other words, is overly agreeable and appeals to the general public by reiterating what we already know. In our world, we might think of Quentin Tarantino or Sabrina Carpenter, individuals who are increasingly pressured to make films and write songs that are maximally palatable rather than creative or inspiring. Because of an overbearing demand to appeal to the broadest possible audience, art becomes predefined, resulting in an artistic universe that has eliminated the need for reflection on a given work of art—in the end, one piece of art begins to resemble the next, and so on.

To Adorno, then, good art must necessarily elicit emotions that lead to a reflection of the world around us. “The less the culture industry has to promise,” he writes, “the less it can offer a meaningful explanation of life.”2 For Adorno, modern art carries only an illusion of novelty, compelling consumers to eschew higher art forms that offer “meaningful explanations of life” and gravitate towards repetitive and redundant works that only confirm their narrow-minded worldviews. This is Adorno’s passive consumer—the modern Western agent satiated by a reiteration of certain easily-digestible patterns that result in a meaningless depletion of leisure time by providing a simulacrum of pleasure in the place of meaningful reflection. Jazz, for instance, is notoriously easy to consume because it repeats familiar tropes; it is “heteronymous” because it is conceived largely with reference to outside political forces. On the other hand, an “autonomous” work of art—the sort of art that Adorno holds in the highest regard—exists only for itself and does not refer to outside political, religious, or economic institutions. This is the sort of art that inspires the greatest degree of critical thinking and the sort of art that, in Adorno’s view, we should aspire towards.

The way for an artist to escape mass commodification is thus to emancipate himself from the universal, to become “mistrustful of style” and to create an original piece of art that requires a more active role on the part of the beholder. In his Aesthetic Theory, Adorno elaborates on his idea of passive art and cites Arnold Schoenberg’s 1912 song cycle Pierrot Lunaire as the quintessential example of a “great work of art”—the sort that escapes commodification and requires active rather than passive consumption. In Adorno’s view, Pierrot Lunaire—the first “modern” work of art—stands in opposition to the monotonous art of the “culture industry” because it defies the prescribed boundaries of Western tonality and offers an experience that is, at first, unpleasant to listen to yet that soon inspires philosophical musings in the mind of the listener. The solution for Adorno, therefore, is to create art that breaks from established societal and artistic norms; art must inspire critical thinking and reveal new ideas both about the world around us and our own selves. Only thus can we escape the denigrating routines of capitalism and start to live our fullest lives.

As I’ve said, I’m skeptical of this Marxist idea that capitalism is fully to blame for the downfall of art. While it is true that capitalism requires artistic sacrifices in order to drive profit, a Marxist system not only requires similar sacrifices but demands them to a far greater degree (consider the Soviet Union and the degree of artistic standardization necessary to maintain order). Capitalism might not be perfect, but it allows for the possibility of art that inspires critical thinking—the sort of art that Adorno holds in the highest regard. Seventy years later, our goal is not necessarily to stop consuming bad art (we all have our guilty pleasure songs, books, and movies) but to engage critically with the media we put in our brains on a daily basis. Not all art is good art, and the first step to defying the culture industry is recognizing that Thomas Hardy or Ernest Hemingway have much more to offer us than Colleen Hoover or E.L. James, for these are the names who cause us to pause, consider, and reflect. In separating good art from slush, we not only carry on Adorno’s legacy but also learn to approach the world with a critical eye: good art, after all, is more than just revolutionary or original—it is also profound and beautiful.

Enjoyed this post? You can Buy Me a Coffee so that I’ll be awake for the next one. If you are a starving artist, you can also just follow me on Instagram or “X.”

The critic Erica Weitzman observes that Adorno simply appears to reject all art that is “fun.”

This sort of passive consumption, according to Adorno, is also responsible for the rise of fascism, where everyone is taught to think the same way.

It strikes me that we are talking about two separate things when we complain about the commodification to mass art (art for mass consumption) and also about the idiocy of modern art. The average person looks at a signed urinal and decides this is stupid, which is why the vast majority of modern art is disdained by the vast majority of people. The reason there is any market at all for modern art is because there is a community of (mostly wealthy, mostly well-educated, often left-wing) types who want to signal their disdain of both “good taste” and “average art.” They intentionally like art which exists solely to defy convention and to “prove” that beauty is a myth and aesthetics are meaningless. I don’t blame capitalism for that, but rather the intentional project on the part of some to reject both traditional aesthetic criteria, and consumerism (to prove that they’re “cultured”).

This isn’t original to me, but a lot of the complaints about mass culture are the same as the complaints going back centuries that the rich had about how poor people have bad taste. When you got an age that produced more democratic art (ie art for the majority population, not just the elites), you ended up with a lot of the cheap, low-brow stuff people disdain as “mass culture.” Why? Because capitalism gives people what they want and this actually does represent what the average human being wants. Most elites can’t come out and say they are snobs who look down on the taste of the poor, because they have to pretend that they’re on the side of the working man/proletariat (including to themselves). But the truth is that the fault isn’t capitalism, but human nature. Not everyone is intelligent or cultured or sophisticated. Like it or hate it, this is what we are.

Finally, Irving Kristol pointed out that the communist countries never produced good communist art. All the good socialist/communist art was produced in capitalist countries. It turns out capitalism really does work better than anything short of oligarchy (Rome, medieval Europe, etc.) at producing art. If more art is produced to meet a growing market for art consumption, the average art will be average, some art will be bad, and some subset of it will be good.

Great essay, thanks. 2 points:

1: Adorno apparently wants art that shows truth about life, but is without reference to politics, economics or any of the other things people care about in life. That strikes me as a problem.

2: I wouldn’t blame capitalism for Marvel slop; the market is punishing them pretty hard for their inability to make movies people want to watch. One might debate why they are such garbage the past 10 years, but definitely capitalism is not to blame for their Marxist creators.

I can’t comment on Taylor Swift… my wife likes her stuff, but it all sounds the same to me, as my music does to her. I can only assume she has terrible taste.