Ambitious Women Aren’t the Problem

What Victorian literature and modern social science reveal about why smart men marry smart women—and why Matt Walsh doesn’t get it.

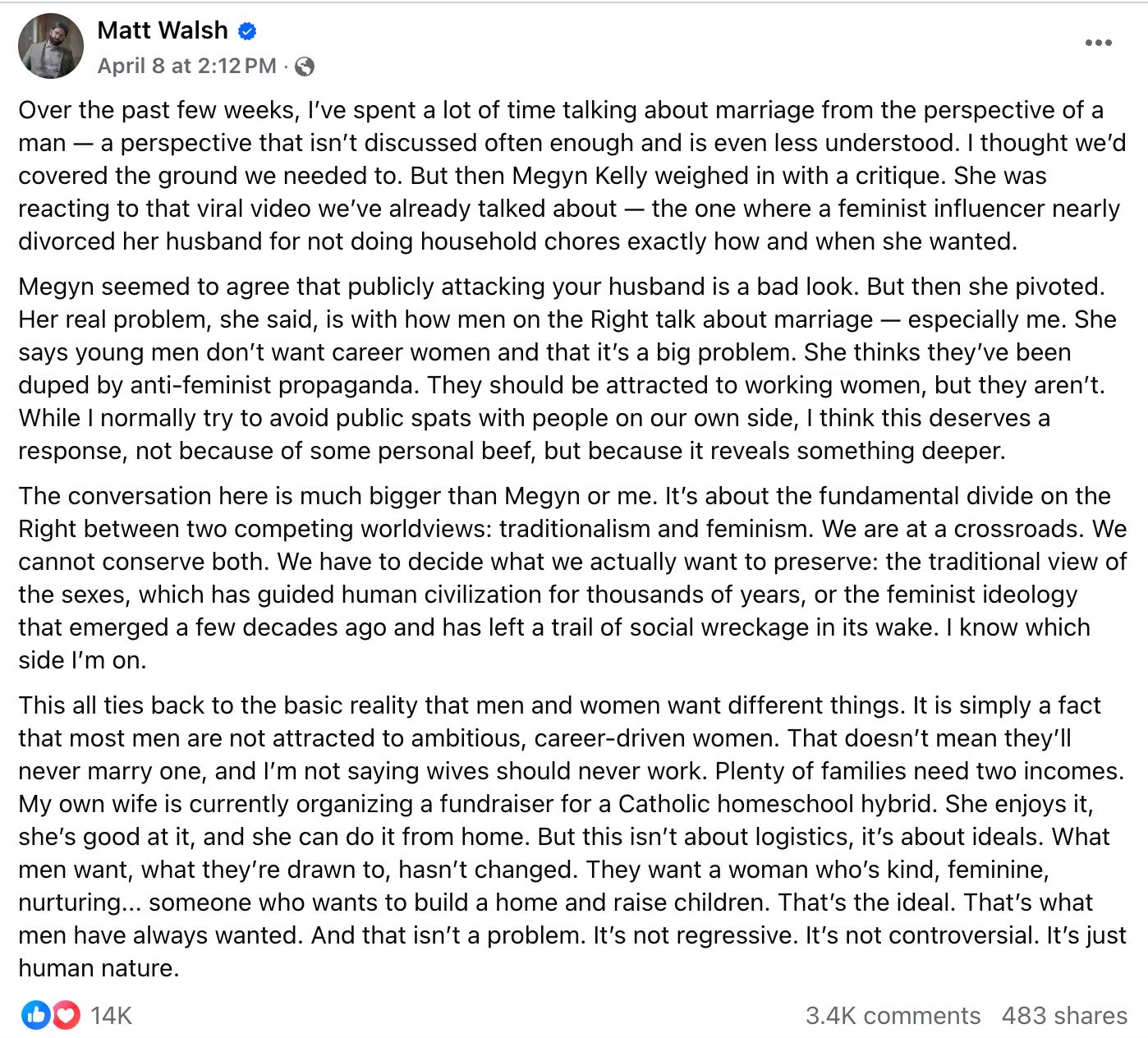

As the societal pendulum swings to the right, an increasing number of men are abandoning women. The latest offense comes from conservative commentator Matt Walsh, who posted the following tirade on his Facebook page last week:

I don’t dislike Matt Walsh. If you haven’t seen his Am I Racist, the #1 documentary of the decade, I highly recommend it. I appreciate Walsh’s deadpan humor and think of him as a sort of conservative comedian. But compared to his compatriots Jordan Peterson and Ben Shapiro at the Daily Wire, Walsh is just not that smart. That is fine. Intelligence is not everyone’s strong suit, and Walsh has a plethora of other positive traits to make up for his lack of book smarts. But what that means is that he assesses “what a man wants” from the standpoint of “what a 100-IQ man” wants, misattributing his aversion to “ambitious, career-driven women” to his desire for traditional values—and completely missing the point about how human beings mate. The fact is that Walsh, seeing the world from the perspective of an average-IQ person who did not go to college and who rose to fame through his comedic bent, assumes that men are not attracted to career women because he himself is not smart enough to understand a career woman.

According to social scientist

, “assortative mating” is far greater for intelligence than for any other behavioral trait. On his Substack, he writes,A study from 2005 that tracked assortative mating in marriages found that if your highest level of education is a high school diploma, your probability of marrying a college graduate is only nine percent. In contrast, if you hold a college degree, your probability of marrying a fellow college graduate is sixty-five percent. This figure is probably higher today.

We know the following: Men who hold college degrees will typically seek partners who hold college degrees as well. College-educated women are much more likely to pursue an ambitious career and live for the pursuit of knowledge than women who only hold high school diplomas. And contrary to what conservatives might have you believe, college is, in fact, correlated with higher IQ, with every additional year of education providing an IQ boost of 1 to 5 points. Therefore, smarter men desire smarter women—and smarter women are more likely to seek out ambitious careers. After all, IQ is also correlated with income.

What these findings tell us is that human beings do not choose their spouses based on who will best carry out each household role. Human beings choose their spouses based on who is most likely to understand them intellectually and emotionally.

I am all for traditional values. The happiest women, after all, tend to be in long-term stable marriages with children. Many women who rage against men or enter non-traditional, polyamorous relationships defy their basic biological impulses, and over half of childless women will eventually regret not having children. I agree with Walsh’s general thesis that it would do us good as a society to revisit traditional marriage values, but I do not believe that this translates to the undesirability of ambitious women or necessitates that women who uphold traditional values be “kind, feminine, [and] nurturing.” A woman can be intellectually fierce, unabashedly ambitious, and also a fantastic mother.

Walsh advocates for a return to a time when women were more docile, but that time has never existed. In fact, we can look to the Western society that most staunchly upheld traditional marriage values—Victorian England—to demonstrate that men have never exclusively desired “kind, feminine, [and] nurturing” women. In a more traditional society, in fact, women who were the most cerebral, capable, and ambitious, tended to be the most desirable because they stood out from the pack.

Unfortunately, I have not enjoyed the privilege of existing in Victorian society, but I have read almost every important work of Victorian literature, and because literature is a close reflection of a particular society’s milieu, we can look to the Victorian greats to understand how intelligent men—the great writers of the era—depicted the typical desirable or marriage-worthy woman.

Perhaps the best example of a Victorian literary woman who is at once sharp and traditional is Bleak House’s Esther Summerson. At the outset of the book, Esther tells us that she is not clever enough to adequately tell her story, but as the novel progresses, we see her grow into a confident, witty, and ambitious woman who manages household deeds, guides moral decisions, and influences the men in power around her. One can only imagine that if women were allowed to hold careers in Victorian society, Esther would have brought sanity to the chaos of Chancery, perhaps even outshining the bumbling lawyers at Kenge and Carboy as they fumble through the Jarndyce and Jarndyce case.

Prefer mysteries? Wilkie Collins gives us Rachel Verinder in The Moonstone. When her fiancé, Franklin Blake, is suspected of stealing her priceless Moonstone, Rachel maintains both her dignity and a level head, leading multiple men throughout the novel to fall in love with her force and charm rather than her aptitude as a housewife—she’s desired because she’s strong-willed and unpredictable.

Or how about the sharp Lady Glencora Palliser from Anthony Trollope’s Palliser series? Lady Glencora, though ambivalent about her marriage, is one of Trollope’s most powerful female characters, pushing her husband’s political ambitions while exerting her own form of power—both in the household and in the public sphere.

There are, of course, many other Victorian female characters written by women—Dorothea Brooke, Jane Eyre, Margaret Hale—who exemplify these traits, but I believe that I have made my point clear: traditional marriage values and ambition are not mutually exclusive. In fact, many young girls would benefit from having a strong female role model in their lives rather than a more docile woman whose sole purpose is motherhood. Motherhood is wonderful. It is not the only noble pursuit for women.

So if Victorian literature teaches us anything, it is that ambition does not make a woman undesirable; men, after all, don't marry “roles”—they marry minds. And while conservative commentators like Walsh have a habit of viewing relationships in purely functionalist terms—a man earns, a woman nurtures—human beings aren’t factory parts. We bond over shared language, emotional depth, and intellectual parity. A man who does not desire an ambitious woman does so not because he wishes to restore traditional gender roles but because he is too dense to understand her. Most men don’t want 1950s housewife cosplay—they want a partner who inspires them, challenges them, and grows alongside them.

In our fractured, chaotic, and valueless culture, I understand better than anyone the need to return to traditional values. But the idealization of docile women—and the rejection of ambitious, intellectually driven ones—is both inaccurate and psychologically shallow. As Victorian literature reveals to us, traditional femininity has always included intellectual sharpness and moral strength. Human beings, after all, are far too emotionally complex to settle for relationships built on role-play alone. Human beings simply desire to be understood.

So no, Matt—ambitious women aren’t the problem. The problem just might be you.

Enjoyed this post? You can Buy Me a Coffee so that I’ll be awake for the next one. If you don’t like buying other people things, you can buy yourself my latest poetry book. Or, if you are a starving artist, you can also just follow me on Instagram or “X.”

Looking for a 1:1 consultation with Liza? Book me out here.

To me it's not really about work, it's about career. Work is about occupying yourself and having income, career is more about status. The left has told women to focus on their careers over everything else, which is very extreme and bad advice, and now some on the right are saying women should be 50's housewives, equally extreme and bad advice.

Intelligence is attractive. Smart people have a good sense of humor, which is just incredibly attractive in a woman. But I do think, as a girlboss yourself, you might be assuming that intelligence and ambition always happen at the same time. I think a lot of ambition is basically hollow. That's something women have known in the past, but it feels like everyone is forced to be ambitious today, forced to market themselves.

The challenge of being an ambitious woman is that most women want men to lead them. Women really want men who are above them. So the higher a woman goes, the fewer men above her there are, the fewer options she has. I think women should keep that in mind. If you're intelligent, you can turn that intelligence into anything. If you put it all into career status, you're limiting your options. So women have to choose, they can't have it all. And smart feminists have always known that, but the feminist message today really is "you can have it all." It discourages women from making decisions.

This is not a decision men have to make. The more career status a man gets, the more attractive he is to women. I don't think women realize how much having a career is often just a way for men to get women.

I have worked with plenty of women in software, and I have noticed that the best female engineers had husbands. I think they got a lot of confidence from their husbands, and that helped them in their careers. So I wish women would reframe their thinking. Instead of focusing everything on career and expecting the relationships to just happen, women should try to marry earlier in their careers and find a husband who supports their career. Men want to feel like we can help women, we want to feel needed. If women don't give men the opportunity to help, to provide value, the resulting relationships are often shallow.

What both sides seem to miss in these debates is the massive role of technology in shaping human roles. I have two DK books, one called Forgotten Arts, which describes field and workshop crafts traditionally performed by men, and the other called Forgotten Household Crafts, which describes crafts traditionally performed by women, though the first book includes a number of women's crafts as well. What this tells us is that for most of history, men and women both practiced a number of physically and mentally challenging tasks that added equally to the wealth of the family. The women's tasks were a little lighter (though most modern men, myself especially, would be exhausted by half a day of traditional women's work), and that they were practiced closer to home, where, of course, the children would have been.

Technological development over the last few millennia has gradually shifted us from a craft economy, in which you largely made things for your own family's use, to a trade economy, in which you made things for sale and brought the things your family needed. That trend greatly accelerated through the 19th and early 20th century, with the effect that it turned the home from a place of production into a place of consumption. All those complex, challenging, productive tasks that had occupied women through the centuries were eliminated. To be productive, a woman then had to leave the home, which, of course, meant leaving her children.

That is the conundrum we find ourselves in today. It was not that women suddenly started to demand challenging and productive occupations after millennia of being content with unproductive idleness. It was that the industrial revolution stripped away the challenging and productive occupations that had been theirs for millennia.

Not that women would want those old occupations back (though they do still do some of them as hobbies). No more would men want their old occupations back. They were a hard slog for rewards that would seem very meager to us today. But men, at least, still leave the household to work as they always did. It is women who have been placed in a bind between going out and leaving their children, and staying at home without adequate occupation. The fabled 1950s were not the end of a long period do domestic bliss. It was a brief episode in the ongoing struggle to adapt to the fact of the home being a place of consumption rather than production -- as was the Victorian struggle over access to the professions.

But perhaps if we were to recognize the role that technology played in bringing this situation about, and acknowledge the genuine nature of the dilemma it creates, we might lower the velocity of the ideological brickbats we hurl at each other's heads.